John Coplans on the Pasadena Art Museum

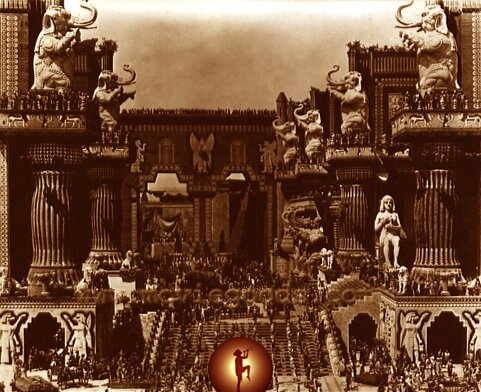

For a brief period in the 1960s, the Pasadena Art Museum (PAM) in suburban Los Angeles staged a sequence of sensational exhibitions of then-contemporary art. New Paintings of Common Objects (1962) is often cited as one of the first Pop Art shows. Exhibitions of Andy Warhol, Richard Serra and Donald Judd followed. Shocking as all this seems now given the staid, conservative character of Pasadena, it was possibly no less so at the time -- especially when director Walter Hopps, with little staff, money or international profile, delivered the world's first ever retrospective dedicated to Marcel Duchamp (seen above).

Within a decade, Hopps and a parade of replacement directors had been fired. The museum was hemorrhaging money and stood on the brink of financial ruin. Having rebuffed the institution's approaches in the past, wealthy capitalist-turned-collector Norton Simon intervened in the spring of 1974. Simon struck a devil's deal; he agreed to pay off PAM's debts on the conditions that 75% of the institution's wall space would be dedicated to his personal collection of Old Master paintings. The existing board of trustees would also be summarily dismissed and a new board created with 10 trustees; Simon would effectively get to appoint 7 of them. This plan was unanimously approved in April 1974. By November 1975, Pasadena Museum of Art had been renamed the Norton Simon Museum.

Artist and critic John Coplans published a scathing chronicle of these events in Artforum in February 1975 called "The Diary of a Disaster." While blame for the loss of Pasadena's then only contemporary art venue is broadly apportioned, Coplans offers a broader indictment of the structure of the artworld. Writing in the wake of Watergate, he puts it like this: "Ever more clearly today, especially because of recent developments on the American political scene, we understand that our institutions depend upon the character and behavior of those individuals who constitute the leadership."

What Coplans catalogues are the routine abuses of the museum's autonomy and institutional controls by power-hungry trustees or by unscrupulous directors who leveraged the museum's collections to raise the prices of their own collections. We read how Eudora Moore, head of the Museum's influential Art Alliance, sabotaged the budding contemporary art agenda with her populist shows of "California Design" that occupied the walls for long periods of time and diverted curatorial energies. Worse still was the tenure as president of the Museum's board of trustees of wealthy collector Robert Rowan who Coplans describes as "one of the most equivocating people it has ever been my misfortune to meet." Rather than hashing out decisions through the designated forum of the board meeting, Rowan mystified his office, secluding it like a latter day Louis XIV into his own private spaces: "He preferred to meet more informally, usually at the Annandale Golf Club, or at his own house. There were lengthy strange meetings, usually over lunch or around social affairs, at which nothing was really decided. Hating arguments, fearing any bad publicity, he either put off decisions or made them privately." This kind of absolutist, personalized rule abrogated the few checks and balances built into the art world, keeping the other board members unsure of how they could act and thus docile.

But, all of this makes for slightly strange reading when we recall that personalized rule is the very kind of thing that Coplans celebrates in the pioneering, maverick tale of Walter Hopps and his single-minded, curatorial vision-making. So, by Coplans' view, the art world seems to work when each category of agent has a dedicated function and sticks to it. Artists make art, curators curate and boards of trustees put up the cash and shut up! Should we really be surprised when, as ever, it doesn't quite work out that way?

Labels: Artworlds, John Coplans, Pasadena Art Museum