Anger/Pater

Talk of truth being stranger than fiction barely covers the odd case that is Kenneth Anger. A child star in the Golden Age of Hollywood, Anger has alternately been a maverick maker of avant-garde films; an intimate of "the Great Beast," Aleister Crowley; a lover of Manson family murderer Bobby Beausoleil; and chronicler of Tinsel Town tittle-tattle in his notorious (and banned) volumes of Hollywood Babylon. His films like Scorpio Rising cut between images of gay biker culture, Nazi propaganda and a Sunday-school film of Christ on the way to Calvary -- all while set to the tune of '50s pop songs like "He's a Rebel." Mick Jagger provided the droning soundtrack to Anger's truly disturbing film Invocation of my Demon Brother (1969), while Anger reportedly put a debilitating spell on Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin when the guitarist failed to produce a serviceable soundtrack for the film Lucifer Rising.

What are we to make of this? Is it all so much ghoulish, drug-addled nonsense? Perhaps cynical, headline-grabbing sensationalism?

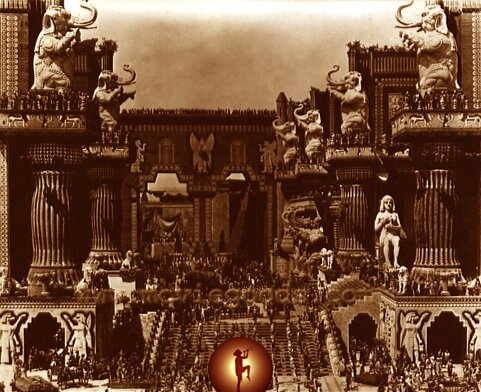

Old Ken recently had occasion to ponder said questions while screening Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954-1966) and perusing bits of Hollywood Babylon, a book that begins with Anger marveling at the ruined set of D.W. Griffith's epic film Intolerance (1916), which we see above in full glory. Under the "Egyptian blue" skies of southern California, Anger muses, an unspectacular cast of petty businessmen and capitalists-turned-filmmakers had dared to recreate Babylon -- to restage the triumphs, the excesses and the cruelties of ancient Mesopotamia. And lured by these baldly commercial business interests, chiselers and chancers from small towns across the country descended on Hollywood where they were transmutated into truly luminous beings: stars.

Among academics, the "star system" is now a standard topic in respectable cinema history. More broadly, we are largely inured to thinking of movie actors as "stars," "idols," or even "gods" of the silver screen. As I engaged with them, I began to feel that for Anger, a character with some very peculiar ideas about gods and idols, these seem to be more than mere facons de parler. What his writings and movies seem to explore is the premise that films are magical spells and that actors should thus be understood as stars in a much older esoteric or Hermetic sense -- as celestial beings connected to elemental forces and wielding supernatural powers.

Consider Anger's entry on Lana Turner in Hollywood Babylon. The chapter begins with a graphic description of the physical, er, endowments of the mobster who Turner took as a lover. We read of their exuberant love-making, her beatings at his hands and ultimately his grisly stabbing by her traumatized daughter. If read literally, all of this might sound like some lurid gossip little better than the tabloids (from which it was, in fact, likely harvested). But, if considered in a more general way, these stories of outlandish virility, sex, violence and explosive rupture of kinship systems read like something directly out of Aeschylus and the "primitive" gods of pagan antiquity.

This, I think, is the point. Anger wants us to pay attention to the ways in which these cinematic luminaries command the power, influence and even language of ancient, pagan beings. Telling in this regard is a journalist's description of Lana Turner which Anger quotes: " 'She is made of rays of the sun, woven of blue eyes, honey-colored hair and flowing curves. She is Lana Turner, goddess of the screen. But soon, the magician leaves and the shadows take over. All the hidden cruelties appear. She is hounded by vicious reporting, flogged by editorials, and threatened with being deprived of her child... '" The woman described her could be Cassandra or other tragic heroines; the point is that such mythical, pagan beings have been (in some important sense) resurrected on and through the silver screen.

Now, there is a rich tradition in the history of art of thinking about these kinds of revivals -- what the famous German cultural historian Aby Warburg called the "rebirth of pagan antiquity" in the Renaissance. From Old Ken's perspective, though, the most powerful of these is to be found in the notorious account of the Mona Lisa set out by Walter Pater in The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873). Because I think this happens to be one of the strangest and most incredible descriptions of an artwork ever, I will quote it at length. Let us marvel together:

"The presence that rose thus so strangely beside the waters, is expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years men had come to desire. Hers is the head upon which all 'the ends of the world are come,' and the eyelids are a little weary. It is a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions. Set it for a moment beside one of those white Greek goddesses or beautiful women of antiquity, and how would they be troubled by this beauty, into which the soul with all its maladies has passed! All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there, in that which they have of power to refine and make expressive the outward form, the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias.

"She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has moulded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands. The fancy of a perpetual life, sweeping together ten thousand experiences, is an old one; and modern philosophy has conceived the idea of humanity as wrought upon by, and summing up in itself, all modes of thought and life Certainly Lady Lisa might stand as the embodiment of the old fancy, the symbol of the modern idea."

What I think Anger's films are trying to do, though, is not just to symbolize these strange forms of persisting divinity but to summon them. This helps to explain the strange nature of the "plots" of many of Anger's more explicitly occult films like Inauguration... and Invocation..., both of which depict rituals and ancient deities. The films are, as Anger stresses, spells that act to connect with and summon these powers.

Labels: Film, Kenneth Anger, Leonardo da Vinci, Magic, Renaissance, Walter Pater

<< Home