A Tale of Two Possets; Or, My Philosophical Dream, Part II

Do you like wine? Many people do. But what do you think of wine when it is combined with sherry? While contemplating that pleasing mixture, let me push you a little further. That is, eggs: do you like them? And cream? Now, what if you were to have the succulent experience of being able to combine all of these ingredients together? Wouldn't that be delicious? No, friend; that would be what I like to call "posset."

Not so long ago, it was Ken's good fortune to be able to try the following recipe for "An Excellent Posset" from the hands of my seventeenth century namesake:

Take a half pint of sack, and as much Rhenish wine, sweeten them to your taste with sugar. Beat ten yolks of eggs, and eight of whites exceeding well, first taking out the cocks-tread, and if you will the skins of the yolks; sweeten these also, and pour them to the wine, add a stick or two of cinnamon bruised, set this upon a chafing-dish to heat strongly, but not to boil; but it must begin to thicken. In the mean time boil for a quarter of an hour three pints of cream seasoned duly with sugar and some cinnamon in it. Then take it off from boiling, but let it stand near the fire, that it may continue scalding hot whiles the wine is heating. When both are as scalding-hot as they can be without boiling, pour the cream into the wine from as high as you can. When all is in, set it upon the fire to stew for about 1/8 of an hour. Then sprinkle all about the top of it the juice of a 1/4 part of a limon [i.e. a lemon]; and if you will, you may strew powder of cinnamon and sugar, or ambergreece [that is, to quote the OED, “a wax-like substance of marbled ashy color, found floating in tropical seas, and as a morbid secretion in the intestines of the sperm-whale. It is odoriferous and used in perfumery; formerly in cookery"] upon it.

Is your mouth watering yet? Well, scrumptious as it sounds, there was some confusions amongst our philosophical community as to whether the posset should be served warm or chilled. Once we tasted the thick, rich concoction cold, it was readily determined that it needed (desperately) to be heated and to be augmented with strong liquor ("fire-water," if you will). Posset and Jack Daniels was offensive to all that is holy; posset and gin was nauseating. In fact, as friend Damo's cautious expression below will suggest, little could be added to posset (with the possible exception of amaretto) to make it pleasing to consume. Some dishes from the seventeenth century, one must conclude a bit sadly, are simply to rich for the effete modern palate.

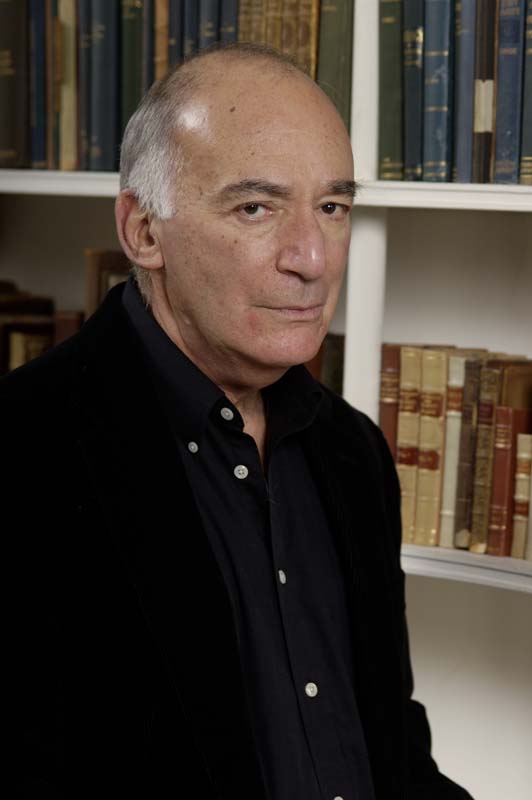

Equally rich but utterly dissimilar in its gustatory pleasures (at least from Old Ken's perspective) was the "scholarly posset" I was so lucky as to be able to sample last night. For, no less a figure than Michael Fried was in the fair city of London, in part to deliver a lecture on contemporary photographer Jeff Wall. As I am sure that this topic may be of interest to you, friend—especially as we await the arrival of Mr. Fried's study of contemporary photography, the provocatively-titled "Ontological Pictures"—I want share my account of the talk. If you want to skip the details and get to the basic "punch-lines" of the talk (as far as I understood them), just scroll to the end.

Mr. Fried began the talk with a discussion of Jeff Wall's photograph entitled "Adrian Walker Drawing from an Anatomical Specimen ...," an image that is mounted on a light-box and displayed on the wall in the manner of an oil canvas. In the photograph, we see Walker seated at full length on a rotating chair in an antiseptic, tiled office. Light pours in from the window we infer must be opposite him. Walker gazes in the direction of the light, as he seems to contemplate the partially finished, red-chalk drawing spread out upon the diagonal drawing board before him. A flayed arm—ostensibly the subject of his drawing—lies before him on a green felt cloth, positioned between Walker's body and the window. As a slight digression, I should note that from the very beginning of the talk, the relations between speaker and artist were framed in a very curious way. Fried quoted passages from Wall's writing wherein the artist explained the ambitions of his work through reference to Fried's scholarship (particularly, the seminal "Absorption and Theatricality"). Fried, meanwhile, quoted lengthy passages from personal letters from Wall, and confessed that the two have become friends. So, to work through Wall's self-conceived debt to Fried, we were treated to a whirlwind review of the major arguments from "Absorption ..." (particularly via reflections on Chardin's "House of Cards," wherein Fried ingeniously argues that the two playing cards which press up against the picture plane—one facing out toward the viewer, the other turned away—emblematize or thematize the structure of the picture itself insofar as it is simultaneously facing outward toward the beholder and yet also turned it, absorbed into its own concerns).

In his historical and critical studies alike, Fried has opposed this kind of "absorptive," rapt attention to within artworks to "theatricality" or the kind of mincing play to the beholder's presence that Fried had so abhorred in Minimalist sculpture. (In a great quote along these lines, Fried described Tony Smith's "Die" [a gigantic black cube that looks like one of a pair of dice without the white dots] as "the enemy of mankind"!) Evocative of this absorptive tradition as Wall's "Adrian Walker ..." is, we are wrong to read the photograph as a candid "snapshot" of someone so engrossed in their activities that they don't detect the fact that they are being made an object of representation. Indeed, as Wall explains, the photographs are re-enactments, theatrical restagings of people in their normal activities—a kind of collaboration between artist and sitter. But does interjection of this theatrical set up do anything to compromise their absorptive power? No, claims Fried. Since the work of Caravaggio and the Carracci in the early seventeenth century, he argues, artists have developed a number of absorptive motifs which can be deployed as a "matrix of realism." It is the "magic of absorption," moreover, that these motifs can be reused and theatrically staged (presumably within certain limits) that they nonetheless still work, still convince us that the sitter in the picture (for example) is not paying any attention to us and is completely engrossed in their own world (despite the fact that they are only present to us by virtue of a representation that is made to be seen).

Having situated Wall within this absorptive tradition, Fried then turned his sights on higher stakes—namely, recuperating Wall and other "ambitious photographers" into the High Modernist project Fried himself had touted in the 1960s and which has subsequently been deemed totally irrelevant to contemporary art. As a slight aside, I should note that Fried made this point by saying something like "High Modernism is not dead; while thus deemed by so-called post-modernism, history has been moving on in its own direction" and all the while snapping his fingerings and making this kind of rotating hand gesture (perhaps an invocation of that old friend, dialectics?). I felt like I was at a beat poetry recital! Anyway, our speaker wanted to develop these larger claims by way of Wall's "Morning Cleaning at Mies Van der Rohe's Pavillion, Barcelona," an enormous (11' x 6') back-lit photograph showing a horizontally-aligned view into the reconstructed Pavilion Mies had built for a World's Fair(?) in the process of being cleaned by a single worker, who washes a window with his back to us. Pardon the crappy description here, but I need to catch a bus soon and I am yet to get to Wittgenstein (eek!). So, Fried makes a really beautiful move here from the engrossed action of the window washer to Wall's writing on the nature of photography in a 1989 essay called "Photography and Liquid Intelligence." There, Wall had elaborated what he saw as the atavistic nature of film photography by virtue of its need for water-based processes, which connected it to dyeing, the melting of ores, and other primordial crafts. As Wall acknowledged in this essay, such "liquid intelligence" was being replaced by the "dry intelligence" of digital photography, whose processes the photographer also made use of in the production of his images.

Should we then read "Morning Cleaning ..." as a kind of allegory of photographic "liquid intelligence"? Maybe, but maybe not, Fried claims. Indeed, like his collaborative method of working more broadly, our speaker suggested, we need to see Wall's work as inseparably binding the intentional and the contingent. And in this way, Fried proposes, his work has particular attentiveness to the everyday. Now, as readers of Fried will know, there are many different variants of "the everyday." In his work on Menzel, we are given an account of the Kierkegaardian everyday, which is posed as a "positive," prehistory to the negative valuations of the everyday given by folks like Heidegger. Well, here, we were treated to the Wittgensteinian everyday and Fried's reading of it based upon a 1930 essay published in a collection called "Culture and Value." There, Wittgenstein is musing that there is nothing more impressive or interesting than to see a man who doesn't known he is being observed. Wittgenstein then proposes a thought experiment: he asks us to imagine a theater where we see a man unaware of being seen. This, our philosopher claims, would be a truly great work of art. Indeed, he continues, only art can give us the individuality of the thing in a way that is worth seeing; such are compels us to see the thing in the right way, and pulls it out of mere nature.

So much for Wittgenstein. Fried then went into a lengthy exegesis of this text, which I will spare you. But, the punch-lines as I understood them were these: 1) despite his specific evocation of the theater in this thought experiment, neither theater nor cinema would have been media capable of satisfying the criteria described by Wittgenstein. Instead, Fried argues, it is the new kind of photography done by friends like Wall that is capable of showing us what is worth seeing in the everyday, or of seeing the everyday "the right way." 2) What this new photography has done is to produce a new, "good" kind of objecthood—a category of being that was utterly unbearable for Fried in essays like "Art and Objecthood." Presumably, it is this capacity of new photographs to rip objects out of the everyday (so to speak) that constitutes their status as the aforementioned "Ontological Pictures." Rich, delicious posset-y food for thought, indeed!

Labels: Art Historians, Experimental, Feast, Michael Fried, Posset

<< Home